The Cycle of Anxiety and Avoidance

Anxiety and Avoidance

Anxiety is a natural physiological response that works to help protect us from real or perceived threats in our environment. A structure in the brain, called the Amygdala, processes emotions and is a key part of the limbic system that is trained to assess for potential threats in our environment. When a perceived threat arises, the amygdala activates our fight or flight systems in response to the danger, which helps to keep us safe. Activation of the amygdala and limbic system can generate many different emotional and physiological responses, including feelings of anxiety or fear (Rasia-Filho, Londero, & Achaval, 2000). The amygdala and limbic system are crucial parts of our survival, however, at times the amygdala can overestimate threats in our environment where there are none.

When we feel anxiety, a common response is to want to avoid whatever is associated with that anxiety, including avoiding things we predict will evoke anxiety. Avoiding can be an effective strategy for temporarily alleviating the anxiety we feel, which can reinforce the strategy of avoiding for use in future anxious situations. Avoiding can be adaptive, as it allows us to avoid a potentially dangerous situation. If the amygdala is overestimating threats in our environment, however, it may be maladaptive by preventing us from engaging in situations that are perceived as dangerous but are actually safe (Ball & Gunaydin, 2022).

One of the challenges with using avoidance as a strategy for managing anxiety is when the amygdala overestimates threats in our environment, we can end up avoiding things that are safe and reinforce maladaptive perceptions. More specifically, by avoiding the situation we are reinforcing to ourselves that the threat was indeed dangerous and needs to be avoided if it emerges again in the future. When that threat emerges again in the future, our anxiety is bigger; we have confirmed the threat is dangerous, reinforced our need to avoid, taught ourselves not to confront the challenge, and subsequently created a deficit in skills to challenge the maladaptive perception of threat and work through the anxiety.

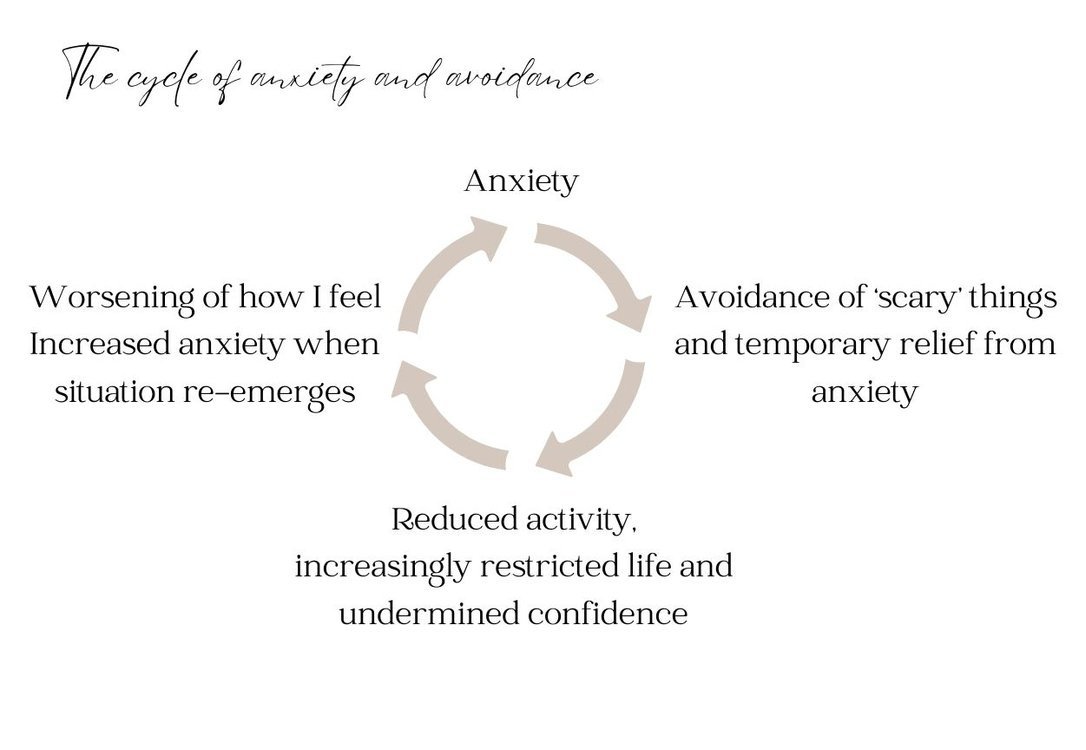

Maladaptive avoidance can contribute to reduced engagement in activities, which can lead to the development of a cyclical pattern of increasingly restrictive lifestyle to manage anxiety, undermining of confidence or self-image, and worsening of how you are feeling (Garland, Fox, and Williams, 2002). This cycle of anxiety and avoidance is depicted in the diagram below (adapted from: Williams et al., 2002).

Adapted from Williams et al., 2002

So how do we teach our amygdala it is overestimating danger and teach ourselves some tools for managing anxiety?

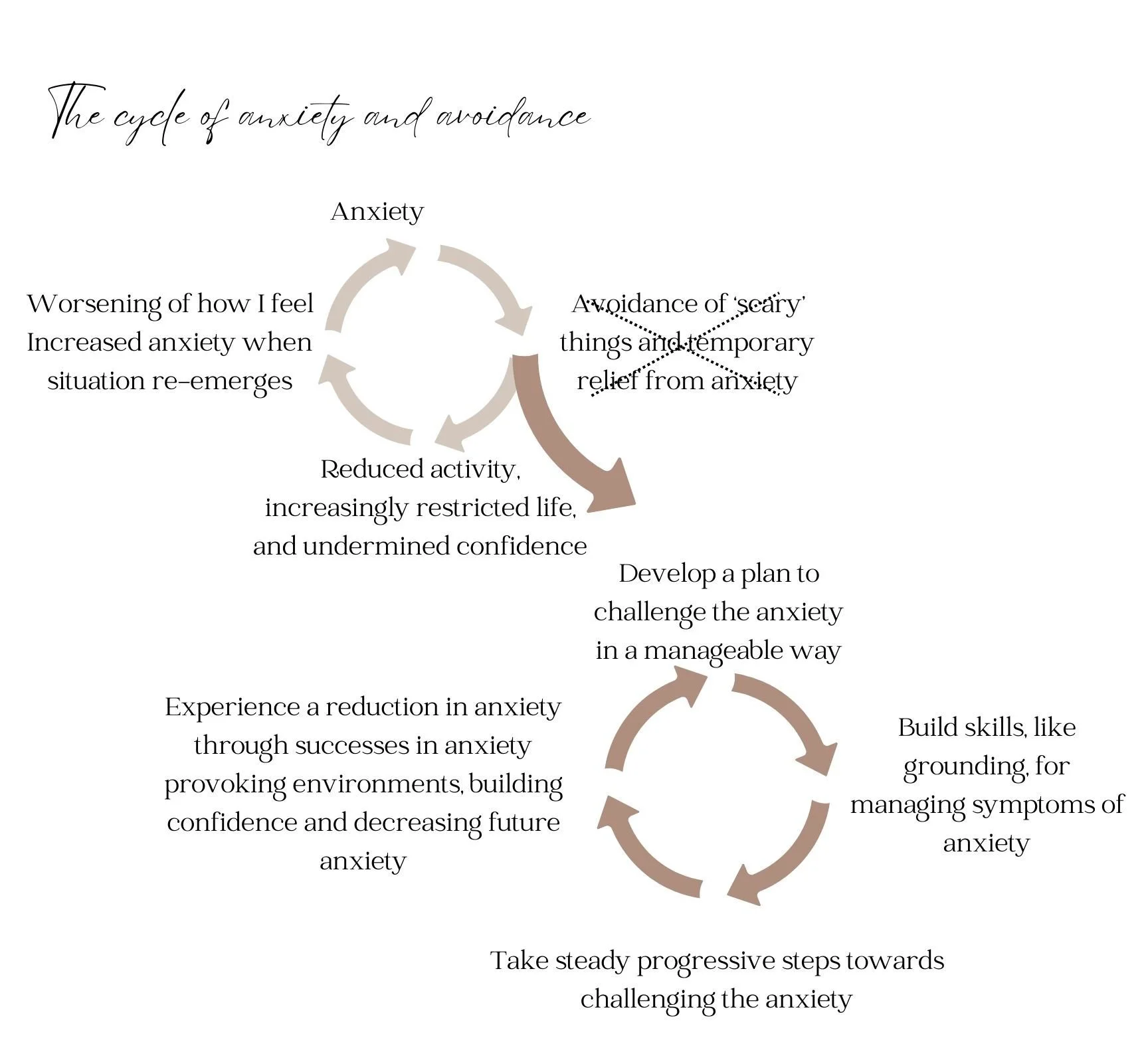

First, we need to recognize the pattern and cycle that is happening. It is important to identify the challenging pattern that you would like to work on and define it clearly. Once the pattern has been identified, it can be helpful to come up with as many solutions as possible and consider the advantages and disadvantages of each solution generated. With a number of different solutions identified, choose one of the proposed solutions. It is important you choose your solution, that can help to promote commitment to and better engagement in the process. Prior to starting to work on your solution, take some time to develop some grounding or coping strategies for when anxiety does emerge. As you begin to work on the steps outlined in the chosen solution, integrate the coping and grounding skills to help manage symptoms of anxiety that emerge. As you progress through the steps of the outlined solution, you will have opportunities to challenge your anxiety, experience small successes with challenging anxiety, and teach yourself that you possess the skills and tools to manage anxiety and the things that you have been avoiding. Experiencing successes with challenging and managing anxiety can build confidence and help reduce the experience of anxiety going forward (Williams et al., 2002). It is important to note that even with grounding and coping tools, anxiety is not something that will disappear or be eliminated completely – it is a natural physiological experience – but we can change how we are impacted by it and the way it is managed. Working with a certified mental health professional, like a psychotherapist, can help with each stage of the above outlined process. This process is depicted in the second circle of the diagram below (Adapted from Williams et al., 2002)

Adapted from Williams et al., 2002

As we go through life we will all naturally experience anxiety, it is the strategies we use to manage anxiety that dictate how we will continue to experience anxiety in the future.

Interested in learning more about the cycle of anxiety and avoidance or therapy services for anxiety? Contact us to inquire about therapy services for anxiety virtually or in-person in Barrie, Ontario.

References

Ball, T. & Gunaydin, L. (2020). Measuring maladaptive avoidance: from animal models to clinical anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41, 978-986. doi: 10.1038/s41386-021-01263-4

Garland, A., Fox, R., & Williams, C. (2002). Overcoming reduced activity and avoidance: A five areas approach. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 8, 453-462. doi:10.1192/apt.8.6.453

Rasia-Filho, A., Londero, R., & Achaval, M. (2000). Functional activities of the amygdala: An overview. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 25, 14-23.

Williams, C., Richards, P., & Whitton, I. (2002). I’m not supposed to feel like this. London: Hodder and Stouton.